Contagious and Courageous Encounters: Indigenous Illness and Survival in Colonial Mexico

The accidental biological advantage of epidemic diseases that spread in the wake of contact with Europeans is cited as a key factor which contributed to the fall of the Nahua, commonly called Aztec, capital of Tenochtitlan. Illnesses such as smallpox, measles, hemorrhagic fevers, and typhus caused tremendous losses of life in Indigenous communities during the colonial period. Historians often explained these events by citing “virgin soils” or as a part of a broader Columbian exchange. Although valuable, these approaches rarely included how Nahuas themselves remembered and survived the horrific loss of life. My manuscript reveals how Indigenous inhabitants of New Spain understood, remembered, and recorded their experiences in uniquely Nahua ways during the major waves of devastating epidemics. In our current moment of COVID recollections and culturally situated responses to pandemics, early modern interpretations are increasingly relevant.

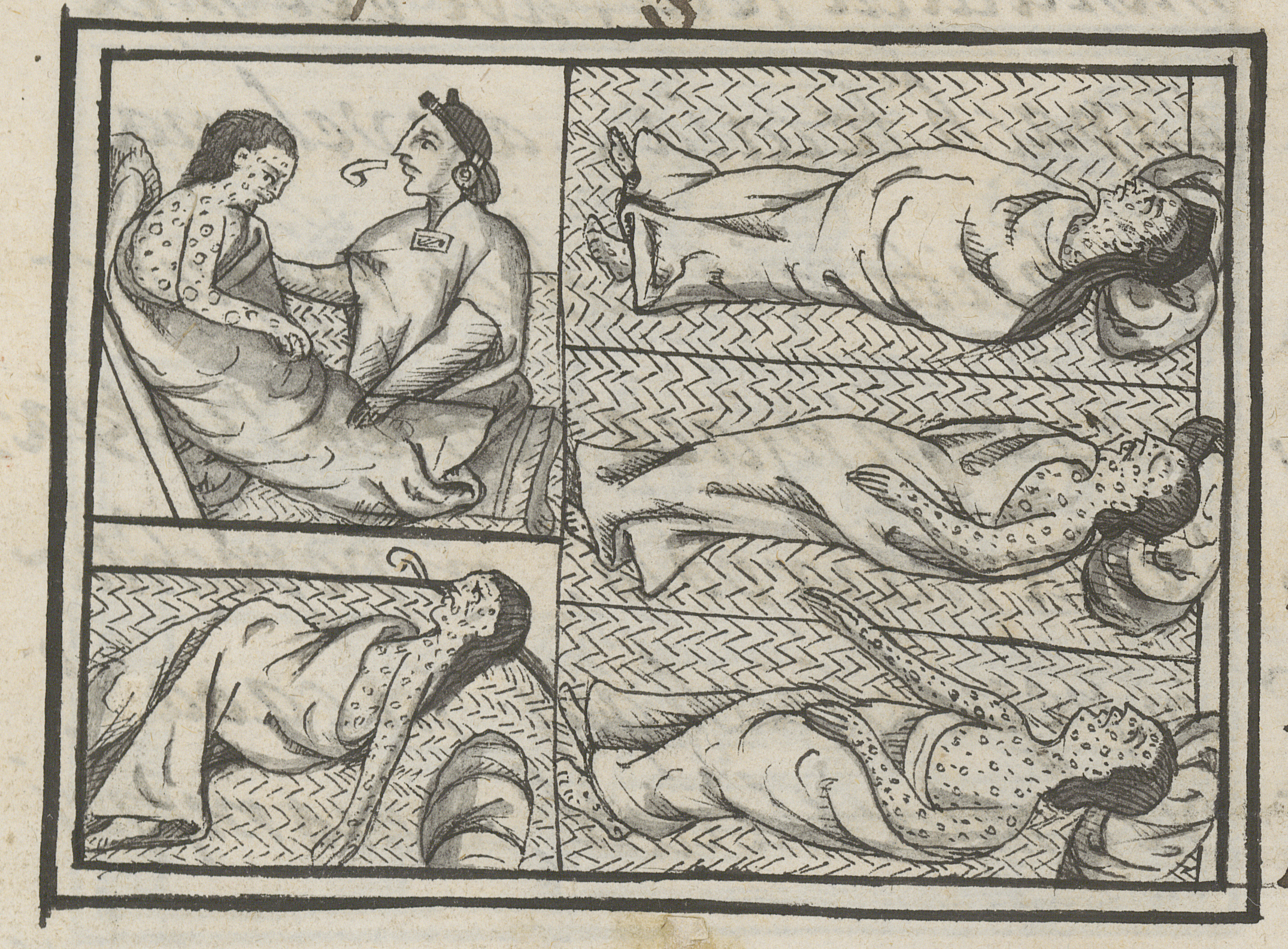

In my study of Nahua (Aztec) concepts of health and sickness in the sixteenth century, I argue that native communities relied on their own terminology and recorded their experiences in uniquely Indigenous ways, despite their immersion in a hostile colonial milieu. In their pictorial histories, Nahua writers, painters, and creators employed Mesoamerican iconographic conventions to portray the desolation of the introduced diseases. During the epidemics that plagued colonial Mexico, Nahuas continued to utilize their concepts of illness to understand the terrible, recurring diseases that caused the deaths of about 90% of their population over the course of a century. The Nahuatl and Spanish texts of the Florentine Codex and the Relaciones Geográficas, in addition to several other pictorial and alphabetic histories, abound with information on a topic that is little explored and poorly understood: how did indigenous peoples comprehend and remember the devastating diseases that were a defining experience of their lives under colonization? How did they associate disease with the arrival of the Europeans, the conquest, Christianity, and Spanish rule? How did they speak and write about these matters? And how did their words on these topics differ from what the Spaniards said? How did Spanish cultural concepts, based on Greek, Roman, and Christian understandings of the body, conform with and contradict Nahua beliefs and practices. What were the implications of the similarities and differences? How did the dominant group attempt to discredit native practices and beliefs regarding health and illness that they considered pagan or superstitious? How did Nahua concepts persevere and survive?

My book addresses these questions for the Nahuas of central Mexico, focusing on the period from 1519 to 1615, a period in which at least three major epidemics devastated the Indigenous population of New Spain. However, my findings are applicable to most parts of the Americas in the early modern or colonial period, up until the early nineteenth century, when nearly all Indigenous peoples in the hemisphere encountered Europeans and Africans and the pathogens that they carried with them across the Atlantic Ocean. Many works have addressed the nature of the epidemics and the extent of the demographic decline, but few studies in Latin American History and related disciplines have endeavored to recover Indigenous voices on diseases that had such long-term consequences for Indigenous survivance.

My book project is currently under contract and the full manuscript is out for review with the series Bodies and Ecologies: Histories of Health, Environment, and Medicine in Latin America and the Caribbean from the University of Nebraska Press.